Clean Energy

Jan 28, 2025

AI’s Power Problem Is Getting Political. Our Answer Starts at Sea.

Youp Overtoom

Contributer

When Belgium starts talking about capping how much power data centers are allowed to use, you know AI’s energy story has moved from “future concern” to “right now problem.”

Over the past months, grid operators and governments across Europe have been sounding the alarm: AI data centers are queuing for capacity faster than grids can be reinforced. Belgium’s grid operator has proposed putting data centers in a separate category with fixed grid capacity, to stop them from crowding out other industries.

At the same time, global AI players are announcing data center plans in the tens to hundreds of gigawatts, and new reports show how quickly this will reshape electricity demand and prices, for everyone.

So what does this mean for AI compute, for renewables, and for a project like ENKI?

The new reality: AI is colliding with grid, land & water limits

Several things are happening at once:

The IEA now projects that data centre electricity demand will more than double by 2030 to around 945 TWh—slightly more than Japan’s total power use today.

AI-specific workloads could account for 35–50% of data centre power use by 2030.

In Europe, installed data centre capacity may only grow ~70% by 2030 because of delays and local grid constraints, even while demand grows much faster.

In some regions, residents are already seeing electricity bills rise as grids invest in infrastructure to serve data hubs, with costs spread across all ratepayers.

On top of that:

Traditional hyperscale sites consume huge amounts of land near cities,

Many still rely on freshwater-intensive cooling, and

Governments are under pressure to protect both industrial competitiveness and climate targets at the same time.

The result: grid connections get slower, politics get tougher, and the cost of “just one more onshore data center” keeps going up.

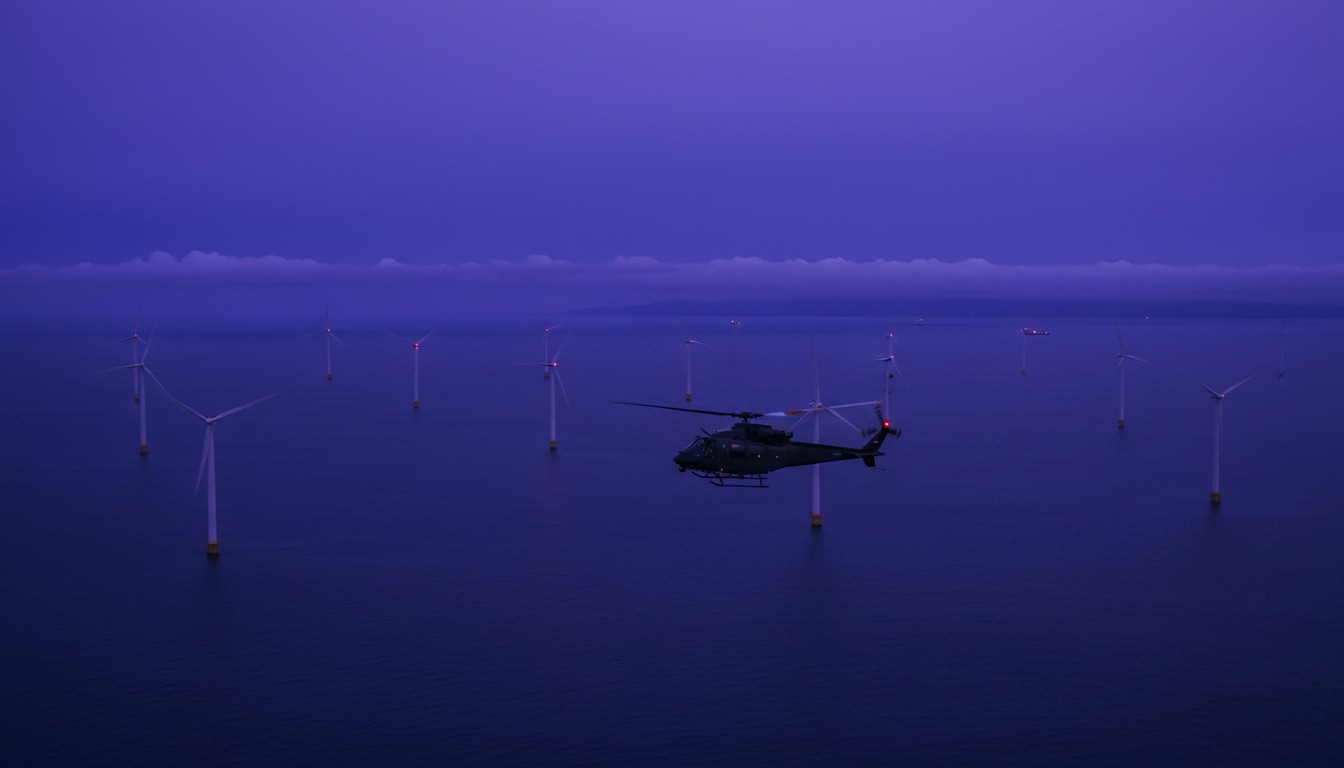

A signal from the water: offshore & subsea data centres are arriving

While caps and constraints dominate headlines on land, something different is happening offshore.

In October, China completed what it calls the world’s first undersea data center directly connected to offshore wind. It runs on over 95% green power, claims 100% water savings and >90% land savings compared to traditional onshore facilities.

It’s not the only experiment, Microsoft’s Project Natick and several barge- or subsea-based concepts have been exploring similar ideas, but it’s a strong signal:

We’re starting to rethink where compute should live in a world of massive AI demand.

This is exactly the question Project ENKI was created to answer. Specifically for AI training and offshore wind in and around the North Sea.

Our vision: move AI compute to the source of renewables

At ENKI, we believe the next wave of AI infrastructure shouldn’t fight the grid; it should relieve it.

Our core thesis is simple:

Put AI compute right next to offshore wind, at sea, instead of forcing more high-density load onto congested onshore grids.

Concretely, that means:

Co-locating AI-only data centre platforms with offshore wind farms

Taking power directly from the offshore substation, not through long, congested transmission paths

Using seawater-based cooling instead of drinking water

Building GPU-dense, AI-native containers, not general-purpose racks

Treating the offshore platform as 20+ year infrastructure, while compute cycles every 3–5 years

We’re not trying to replace onshore data centres. We’re building a new layer:

AI-native, at the grid edge, tuned for training workloads, and designed to unlock stranded renewable potential.

A model project: our 100 MW North Sea offshore AI campus

To make this tangible, we’ve modelled a flagship project concept: a 100 MW offshore AI campus in the North Sea, co-located with an existing wind farm.

How it works (at a high level)

Power

Up to 100 MW of AI training load, fed directly from the wind farm’s offshore substation.

Long-term green power agreement, avoiding onshore grid bottlenecks and speculative queueing.

Cooling

Closed-loop seawater cooling with strict temperature control to keep return flows within regulatory limits.

No use of drinking water for cooling.

Compute

Modular 1 MW GPU container blocks (high-density racks, liquid or direct-to-chip cooled).

Designed for training-only workloads: large models, long runs, high utilisation.

Connectivity

Dedicated subsea fiber to major European internet exchanges, keeping training close to data sources and users.

The modeled impact

Using conservative assumptions, a 100 MW offshore AI campus like this can deliver:

~800 GWh of offshore wind used annually for AI training, much of it that might otherwise be curtailed or sold at very low prices.

~1.6 billion liters of drinking water saved per year compared to a typical land-based, water-cooled AI data center of similar size.

0 hectares of new land taken up near cities or industrial hubs.

Up to ~240,000 tonnes of CO₂ emissions avoided per year compared to running the same load on a fossil-heavy grid mix (assuming ~300 gCO₂/kWh).

For the AI compute partner, this translates into:

A pathway to scale training capacity without standing in long grid connection queues

Lower and more predictable €/MWh for a large share of their workload

A credible sustainability story that doesn’t rely solely on offsets

For the energy partner, it means:

A baseload offtaker that can absorb power when prices are low

Reduced curtailment and improved project economics

A way to show that large-scale renewables directly power critical digital infrastructure

Why this matters in a world of caps and constraints

If countries like Belgium move ahead with fixed grid capacity allocations for data centres, and others follow, AI companies will have to start asking a different question:

Instead of “Where can I plug into the grid?”,

“Where can I plug into generation?”

We see three big advantages to this shift:

Less friction with local communities

No land grab near cities

No visible new mega-buildings

No competition with housing or industry for space

Less pressure on water resources

Offshore projects can be designed to use no potable water at all, with careful thermal management.

A better fit with climate goals

Data centres become direct, controllable sinks for green power, not just another load on the grid.

It becomes easier for policymakers to say “yes” to AI capacity that is clearly tied to additional renewables.

Our takeaway: AI needs to grow differently, not just bigger

The recent headlines about AI’s power demand, rising bills, and countries considering caps aren’t just noise. They’re early warnings that the “old” way of deploying compute is running into physical and political limits.

Our conviction at Project ENKI is that:

AI will keep growing.

Grid and water constraints will keep tightening.

The only scalable answer is to rethink location and architecture, not just add more megawatts to the same places.

By moving AI compute offshore, next to wind, we can:

Unlock new green capacity without overloading urban grids

Dramatically reduce land and water footprints

Create a more secure, physically isolated environment for critical AI workloads

And we can do it in a way that’s modular, scalable, and repeatable across multiple wind parks and regions.

If you’re building or buying large-scale AI compute and wondering where your next 50–200 MW will actually fit, our view is simple:

The next generation of AI infrastructure won’t just be bigger.

It will be offshore.

Ready to Take Your AI Compute Offshore?

Project Enki B.V. | a TJYP Venture

Chamber of commerce: 98681036

Ready to Take Your AI Compute Offshore?

Project Enki B.V. | a TJYP Venture

Chamber of commerce: 98681036

Ready to Take Your AI Compute Offshore?

Project Enki B.V. | a TJYP Venture

Chamber of commerce: 98681036